1. Fruitvale Station: I like the story of this movie and the fact that the story didn't

specifically point out racism. The acting in the movie was great and very

realistic and I felt I could relate to the story.

2. O, Brother Where Art Thou: This was the second time I saw this movie and the

reading helped me appreciate the movie more. I enjoyed the soundtrack/score; it

seemed to add more to the movie. The Odyssey is one of my favorite stories and

I think the way that the Coens reinvented the story was unique.

3. Killer of Sheep: The acting in this movie wasn't particularly good, but I liked the

message of the movie and the way the movie was shot. The cinematography seemed

to add more to the film and what it was about because it was imperfect. I

thought it was a very realistic representation of the black ghetto.

4. Moonrise Kingdom: I really love the cinematography and choreography of the scenes in

this movie. It was quirky and I feel that it captured the essence of the

childhood in a weird quirky way.

5. Awara:

Even though this movie was black and white, when I play back scenes from this

movie in my head I see the scenes in color. I think this movie sort of embodied

Bollywood (for me). I felt the exaggeration of the acting combined with the

dramatization of the music made this movie colorful.

6. Freaks:

The message in this movie was good and I like the way that the story took place

in a circus even thought the setting could have been in a more traditional

setting; the setting made the story more unique.

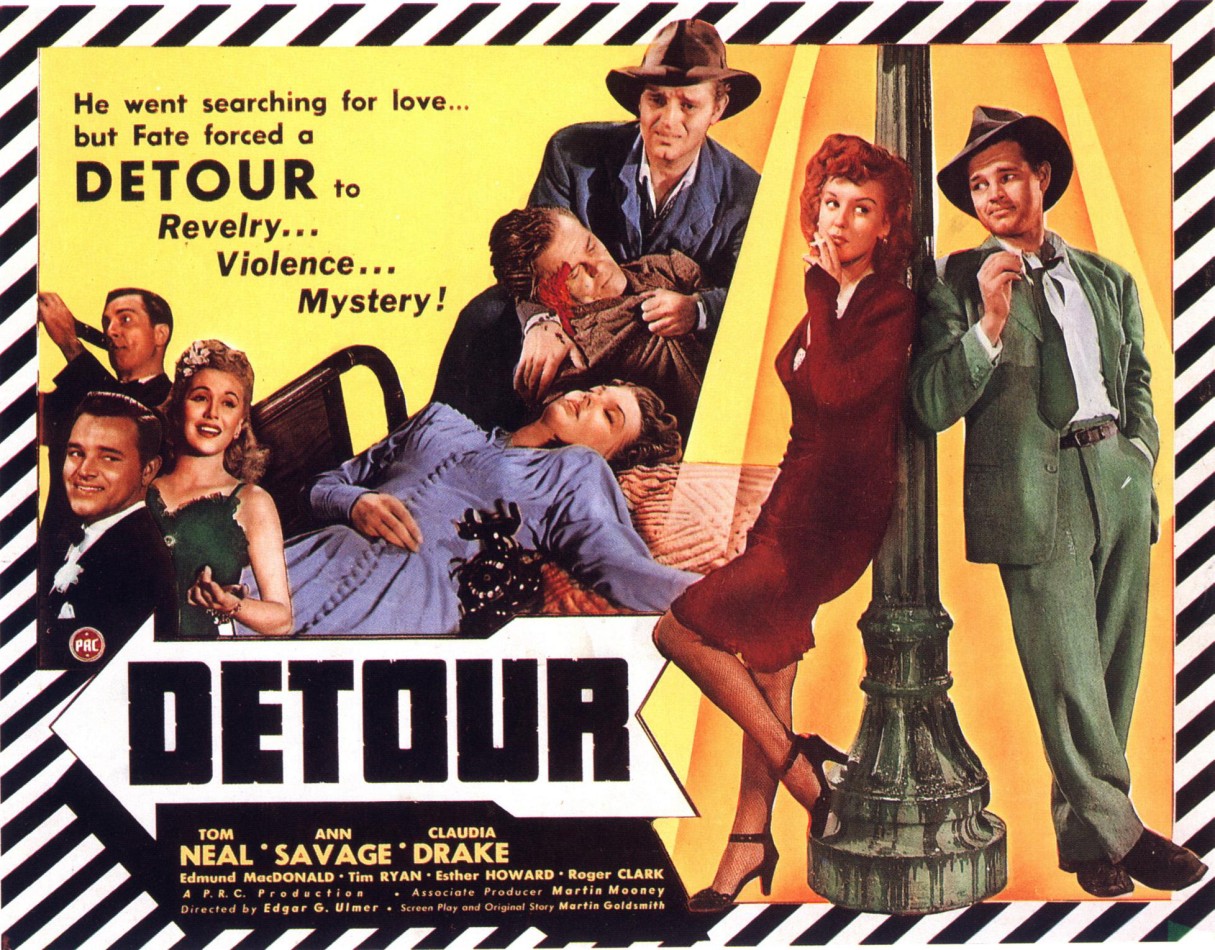

7. Detour:

I really liked this movie because it reminded me of Carmen Jones (one of my favorite movies). I like the story of the beaten

down hero turned antihero and how Vera dies.

8. The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: This was my third time seeing this movie and

enjoyed it more than I did before, but the dubbing in the movie still prevented

me from liking it 100%. I appreciated the aesthetics of the movie after watching

it this time.

9. Wendy and Lucy: I like the message of this movie and the fact that the message was

delivered subtly. I found the movie very slow and felt the message/story could

have been told differently.

10. My Own Private Idaho: I feel like this would have been a great movie if

I were a stoner. I wasn’t particularly fond of the acting, especially the scene

when River Phoenix tells his brother that he knows who his father is.

11. Sherlock, Jr.: I am not a big fan of slapstick comedy, and I felt that the parts

that are supposed to be funny are ridiculous. I guess it is just that times

have changed and what was funny then, is not funny now.

12. Spoorloos: The sequencing of the story made it more interesting, but if it had

not been for that I would have hated this movie completely. This was the only

movie in the sequence I would say that I disliked, plus I felt it was kind of

sappy.